Monarchs and Milkweed

The beauty and amazing migratory journey of the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) has captivated the public’s interest. But threats to its survival — including habitat loss, pesticide use and frequent roadside mowing — have created concern and a desire to help. Unfortunately, some of our efforts may be causing more harm than good.

Scroll down to learn more.

Monarchs in Florida

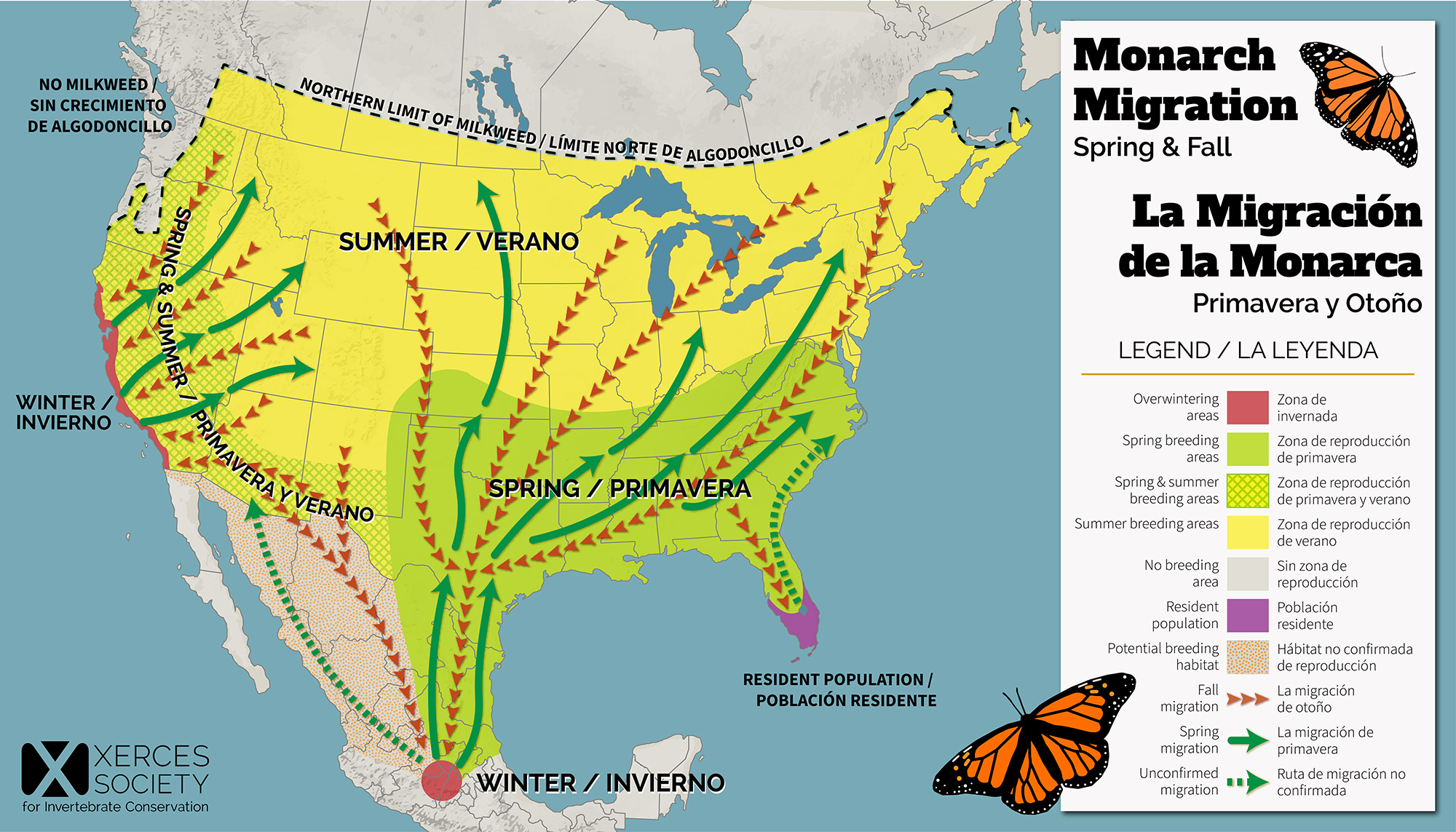

Historically, the Eastern migratory population of Monarchs moved through the Panhandle and North Florida on its annual journey. However, in recent years, some butterflies have deviated from their southwest route toward Mexico, traveling down Florida’s peninsula instead. While it is unclear where these butterflies ultimately end up, it is believed that some may cross the Gulf of Mexico, others may continue south into the Caribbean, and some may settle in South Florida, where a non-migratory population resides.

Beyond its significance in the migration route, North Florida also serves as part of the spring breeding range of Eastern migratory Monarchs. Meanwhile, South Florida has seen a notable surge in its non-migratory population. This surge is largely due to the widespread planting of non-native Tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) and the practice of butterfly rearing. Although these efforts are well intentioned, they have inadvertently created ecological and health risks for Monarchs — risk explored in detail below.

Learn more about these complex issues in this webinar from Dr. Jaret Daniels: Milkweed, Monarchs and OE in Florida: It’s Complicated

How you can help

In Florida, you can support Monarch butterflies by providing fall-blooming nectar plants for migrants, planting Florida’s native milkweeds for North Florida’s spring-breeding population and South Florida’s year-round population, and advocating for reduced mowing on roadsides.

The use of Tropical milkweed in landscapes is not recommended. If you currently grow it, consider removing it and replacing it with Florida native milkweed and other native nectar plants.

Nectar for Monarchs

Plant these natives along with native milkweed to provide nectar for Monarchs:

- Blazing star (Liatris spp.)

- Snow squarestem (Melantherea nivea)

- Chaffhead (Carphephorus spp.)

- Climbing aster (Symphyotrichum carolinianum)

- Frostweed (Verbesina virginica)

- Flattop goldenrod (Euthamia caroliniana)

- Goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

- Mistflower (Conoclinum coelestinum)

- Scorpiontail (Heliotropium angiospermum)

- Beggar’s tick (Bidens alba)

- Yellowtop (Flaveria linearis)

Why plant native?

Florida’s native plants have evolved here over thousands of years. They have symbiotic relationships with the wildlife and ecosystems around them, and have adapted to Florida’s unique climate, pests and soils. When the right plant is used in the right place in planted landscapes, they typically don’t need fertilizers or insecticides, or additional water once established.

Native milkweed

There are 21 milkweed species native to Florida. The three native species featured below are generally available at Florida native nurseries.

Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) is the most widely recognized native milkweed. Its showy clusters of bright reddish-orange flowers bloom late spring through fall. This native wildflower grows 12 to 15 inches high in a bushy form and has coarse lance- or oval-shaped leaves. Because it grows naturally in sandy habitats, it adapts well to dry landscapes.

Pink swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) is found in moderate to moist sunny habitats, where it grows 2 to 4 feet tall. It blooms in summer with very showy light pink- to rose-colored flower clusters. Its fleshy linear leaves grow up to 6 inches.

White swamp milkweed (Asclepias perennis) is a shorter bushy plant growing to about 2 feet. Summer flowerheads are small with white to light-pink flowers. Bright green leaves are lance-shaped. It prefers moist to wet soil conditions and can adapt to shady locations.

DID YOU KNOW?

Queen and Soldier butterflies also use native milkweeds as host plants for their caterpillars, and Pipevine, Spicebush and Eastern swallowtails rely on them for nectar. Many other butterflies and bees — including native sweat bees, leafcutter bees and yellow-faced bees — need milkweed’s pollen and nectar.

Pictured: Pipevine swallowtail on Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) by Mary Keim

Why aren’t native milkweed plants widely available?

Although they are robust in Florida’s natural habitats, native milkweeds can be difficult to propagate. Because they are a larval food source, butterfly larvae may devour milkweed foliage before the plants can be brought to market.

What we are doing

The Florida Wildflower Foundation, along with partners such as the Florida Museum of Natural History and Florida Association of Native Nurseries, is working to increase native milkweed production by supporting the sustainable collection of seeds from wild populations and the testing of propagation methods in order to develop and share best practices.

Where to purchase native milkweed plants

Act responsibly

Digging up wild native milkweed and collecting seed can reduce its ability to reproduce.

- Do not attempt to dig up wild native milkweed plants.

- Do not collect wild native milkweed seed unless you have permission from the landowner.

- If you have permission to harvest, take no more than 10 percent of the available seed.

How Tropical milkweed harms Monarchs

Tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) is now designated as a Category II invasive species by the Florida Invasive Species Council. Although popular and widely available in nurseries, it is not native to Florida. Native to Mexico and Central America, it can escape cultivation and spread into natural areas where it may alter local plant communities and contribute to ecological disruption. Its invasive designation underscores the importance of replacing it with Florida native milkweed.

In addition to its invasive potential, Tropical milkweed poses significant risks to Monarchs.

It contributes to the spread of OE (a Monarch parasite)

Because Tropical milkweed remains leafy year-round in Florida’s temperate climate, it creates ideal conditions for the parasite Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE) to persist and accumulate. Adult Monarchs infected with OE carry microscopic spores on the outside of their bodies, especially on the abdomen. When they land on milkweed, they transfer spores onto leaves, where caterpillars ingest them while feeding. Adults also deposit spores on their eggs, and OE can be transmitted sexually between mating butterflies. Once ingested, the parasite multiplies inside the caterpillar. Infected Monarchs may emerge weak, deformed, unable to fly well — or unable to fly at all — and they often have shortened lifespans.

Florida is a hot spot for OE because Tropical Milkweed does not die back seasonally. Native milkweed species naturally go dormant in winter, breaking the parasite’s cycle and helping reduce spore buildup. Learn more about OE concentrations here. Find out if Monarchs in your area are infected and help contribute to ongoing research by participating in Project Monarch Health.

It can disrupt migration

Tropical milkweed is evergreen and may bloom throughout winter, encouraging migratory Monarchs to overwinter in Florida and breed continuously. This disruption of their natural life cycle makes them more vulnerable to cold snaps and winter food shortages. Overwintering Monarchs are also more susceptible to OE, which persists and accumulates in Tropical milkweed throughout the winter.

It may expose Monarchs to harmful insecticides

Tropical milkweed is often grown and sold as an ornamental “butterfly” plant, and many commercially grown ornamentals are treated with systemic insecticides such as neonicotinoids. These chemicals keep pests off of the plants, giving them a better appearance at retail nurseries, but they also persist in plant tissue — including leaves, stems and nectar — and can poison caterpillars feeding on the treated plants. Exposure to systemic insecticides can reduce survival, impair development and lower reproductive success. (Learn more in this study: Target and non-target effects of insecticide use during ornamental milkweed production, published in June 2024.)

It is prone to aphid infestations.

Tropical milkweed’s lush, evergreen growth makes it particularly attractive to aphids. Heavy aphid pressure can reduce the number of eggs Monarchs lay on a plant and limit the foliage available for caterpillars. It also often leads nurseries — and well-intentioned gardeners — to use systemic insecticides that can persist in the plant and harm caterpillars. Aphid feeding may also trigger elevated cardenolide levels, further affecting caterpillar development.

It reduces reliance on native species

When Tropical milkweed is widely planted, Monarchs may choose it over native species that better support their long-term health and ecological relationships. Tropical milkweed can also contain higher levels of cardenolides than native milkweed species. While Monarchs depend on these compounds for protection, unusually high or unseasonal cardenolide levels may stress caterpillars or affect their development.

Impact of butterfly rearing

Raising and releasing Monarchs can be a well-intentioned activity, but it carries several risks for wild populations. Captive-reared butterflies may have compromised genetics and reduced fitness, which can make them less healthy and impair their natural migratory orientation. Rearing at high densities can also increase the spread of diseases and parasites, such as Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE), which can then be introduced into wild populations. Once released, it is difficult for researchers to distinguish reared Monarchs from naturally occurring individuals, making it harder to accurately monitor population trends, migration routes, and overall population health. For more information, check out the Joint Statement on Captive Breeding, issued by the Xerces Society and other research institutions.